THe Countrey Parson is full of Charity; it is his pre- dominant element. For many and wonderfull things are spoken of thee, thou great Vertue. To Charity is given the covering of sins, I Pet. 4. 8. and the forgivenesse of sins, Matthew 6. 14. Luke 7. 47. The fulfilling of the Law, Romans 13. 10. The life of faith, James l. 26. The blessings of this life, Proverbs 22. 9. Psalm 41. 2. And the reward of the next, Matth. 25. 35. In brief, it is the body of Religion, John 13. 35. And the top of Christian vertues, I Corin. 13. Wherefore all his works rellish of Charity. When he riseth in the morning, he bethinketh himseife what good deeds he can do that day, and presently doth them; counting that day lost, wherein he hath not exercised his Charity. He first considers his own Parish, and takes care, that there be not a begger, or idle person in his Parish, but that all bee in a competent way of getting their living. This he effects either by bounty, or perswasion, or by authority, making use of that excellent statute, which bindes all Parishes to maintaine their own. If his Parish be rich, he exacts this of them; if poor, and he able, he easeth them therein. But he gives no set pension to any; for this in time will lose the name and effect of Charity with the poor people, though not with God: for then they will reckon upon it, as on a debt; and if it be taken away, though justly, they will murmur, and repine as much, as he that is disseized of his own inheritance. But the Parson having a double aime, and making a hook of his Charity, causeth them still to depend on him; and so by continuall, and fresh bounties, unexpected to them, but resolved to himself, hee wins them to praise God more, to live more religiously, and to take more paines in their vocation, as not knowing when they shal be relieved; which otherwise they would reckon upon, and turn to idlenesse. Besides this generall provision, he hath other times of opening his hand; as at great Festivals, and Communions; not suffering any that day that hee receives, to want a good meal suting to thejoy of the occasion. But specially, at hard times, and dearths, the even parts his Living, and life among them, giving some corn outright, and selling other at under rates; and when his own stock serves not, working those that are able to the same charity, still pressing it in the pulpit, and out of the pulpit, and never leaving them, till he obtaine his desire. Yet in all his Charity, he distinguisheth, giving them most, who live best, and take most paines, and are most charged: So is his charity in effect a Sermon. After the consideration of his own Parish, he inlargeth himself, if he be able, to the neighbour-hood; for that also is some kind of obligation; so doth he also to those at his door, whom God puts in his way, and makes his neighbours. But these he helps not without some testimony, except the evidence of the misery bring testimony with it. For though these testimonies also may be falsifyed, yet considering that the Law allows these in case they be true, but allows by no means to give without testimony, as he obeys Authority in the one, so that being once satisfied, he allows his Charity some blindnesse in the other; especially, since of the two commands, we are more injoyned to be charitable, then wise. But evident miseries have a naturall priviledge, and exemption from all law. When-ever hee gives any thing, and sees them labour in thanking of him, he exacts of them to let him alone, and say rather, God be praised, God be glorified; that so the thanks may go the right way, and thither onely, where they are onely due. So doth hee also before giving make them say their Prayers first, or the Creed, and ten Commandments, and as he finds them perfect, rewards them the more. For other givings are lay, and secular, but this is to give like a Priest.

Just a few notes on Charity:

- It is done in ways that maintains dignity, through giving work or selling at reduced rates.

- It should be given in a way to avoid it being expected or obligated.

- The minister takes the initiative and lead personally before preaching it.

- Though it should start in the parish, it should extend beyond the bounds if resources allow.

- It should be given in a way that reinforces good living.

Question for the ministers: What policies does your church, or what practices do you personally have about providing charity in your local community?

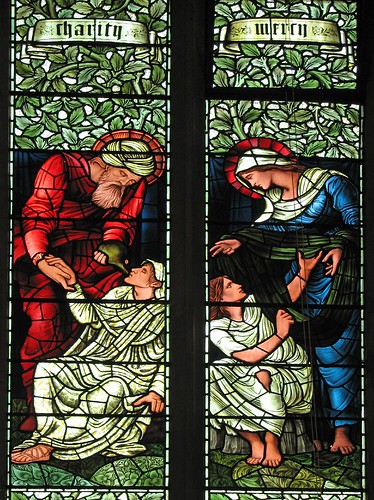

(Image is Charity & Mercy by Lawrence OP: click on picture for his Flickr site)